Story and photos by Cheryl Hartz

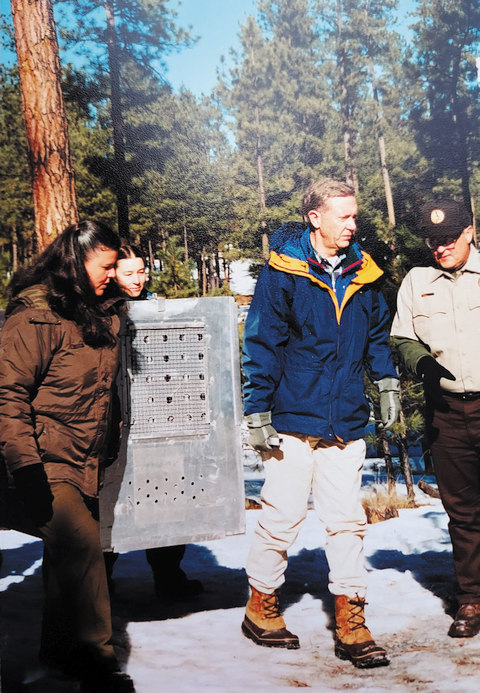

In the deep snow of the Apache National Forest, over 80 people kept absolutely still as a former Arizona governor and 11 others carried three metal cages to a tall chain link enclosure.

Metal bars screeched in the silent wilderness as cage doors were slowly opened. In seconds, a large gray creature leaped out and began exploring her new world. In a few weeks, after she got used to the woods, the enclosure would be opened and she would be free!

This long awaited return of endangered Mexican gray wolves to Arizona happened in January, 1998, with just three wolves: a mated pair and their female pup. They were the first free wolves in Arizona since 1970.

More were released as the months passed. The wolves began to establish packs and have their own pups. Sometimes foster pups were placed in with the wild ones. The mothers also accepted those babies as their own. This year, a record 27 pups were fostered. At the end of 2023, at least 257 wolves in 60 packs now roam the two million acres of Arizona and New Mexico’s Apache-Sitgreaves National Forest.

The successful reintroduction of this most endangered subspecies of North American gray wolves wasn’t easy.

No known Mexican wolves existed in the wild. Wildlife experts were able to expand the number from only five captive wolves to 150 before our government seriously began returning wolves to the wilderness.

The efforts of Defenders of Wildlife, Arizona and New Mexico Game and Fish Departments, the San Carlos Apache Tribe, the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Services, the American Zoological Society, AZA Saving Animals from Extinction, and many many others made it possible for formerly captive wolves to live in the wilderness. They held meetings with people who live near the areas where the wolves would be released, to make sure everyone knew what to expect. They listened to the concerns of the area’s residents.

Wolves are important predators in their ecosystems. They eat mostly deer and elk, keeping those populations from becoming too large. But early settlers believed the wolves ate too many of their cattle and sheep, so they hunted them.

Many populations of red and gray wolves were wiped out, with Minnesota having only a few hundred gray wolves. The most well-known effort to put wolves back in the wild happened at Yellowstone National Park. It now has at least 124 wolves in 10 packs. Not as well known, less than 20 red wolves – the rarest of all wolves – roam wild in North Carolina after reintroduction.

Not everyone is in favor of returning wolves to the wild. Some ranchers worry their livestock is not safe. But a program to help the ranchers was put in place at the start. If biologists confirm that a wolf killed a cow or a sheep, the rancher gets money to replace it. But wolves aren’t the only animals to prey on livestock. Bears, coyotes, mountain lions, bobcats and wild dogs also are predators.

Most people will never see a wolf in the huge expanse of wilderness. Wild wolves avoid humans. But it’s exciting to know they are out there, being part of Wild Arizona.